As the end of the year approaches, here are some of the best things that I have read, seen and heard in the past twelve months.

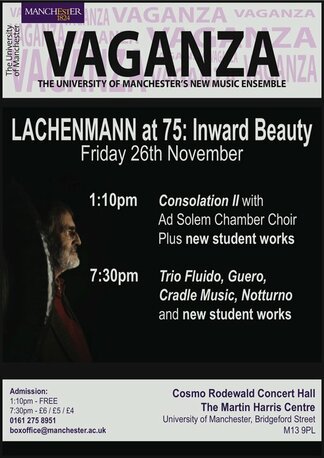

Two major, large-scale performances this autumn made an impact on me. The London Sinfonietta’s concert of Lachenmann at the Southbank Centre in October was one. I already knew the monumental piano concerto Ausklang was something special, but the highlight that evening was Schreiben, a 25-minute orchestral work from 2003. Here’s the beginning of that performance recorded by Radio 3:

The other large-scale performance that is still burned into my memory came courtesy of musikFabrik and their performance of Rebecca Saunders’s CHROMA at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in November. A work of vast scope and many beautiful intricacies, I found myself deeply moved by the experience of wandering through that architectural sound. Here’s a short video from rehearsals at Huddersfield Town Hall featuring probably the creepiest of Saunders’s collection of music boxes — music boxes that together produce a kind of glittering, metallic rain:

On a smaller scale, I was very impressed by Punto rosso, the second string quartet by Brazilian composer Aurélio Edler Copês, performed by Quatuor Diotima at this year’s Centre Acanthes in Metz. Using live electronics to great effect, the work offers a rich and intensely colourful soundworld that unfolds to form a powerfully organic structure. Here’s an excerpt:

Going back to the beginning of the year: Amir Nizar Zuabi’s play I Am Yusuf And This Is My Brother, performed by Palestinian theatre group ShiberHur at the Young Vic in February, was poetic not only in its language but in its staging. Written around the upheaval visited upon a Palestinian village during the conflict in 1948, the footprints left in the dust on stage by the continually fleeing actors was as elegant a visual metaphor as the old man bearing the weight of an uprooted tree that he planted, watched grow, and does not wish to abandon. Here’s a short interview with the playwright from The Guardian:

Olafur Eliasson’s exhibition Innen Stadt Außen at the Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin this summer was mind-blowing in its simplicity and effectiveness. I suppose that means it was efficient, but that seems a crude way of describing installations that created some seriously beautiful experiential situations such as these snapshots of lighting created with strobe light and flailing hose (this video’s from the Venice Architecture Biennale:

See also this piece of video art that lent the exhibition its name.

The death of Tony Judt in August left us without one of the most perceptive, calm and original thinkers on politics and history of recent times. As his motor neurone disease worsened, his output became all the more urgent and Ill Fares The Land, published in March, is an astonishingly clear-sighted and keenly argued book on the state and future of British and US politics. The paperback isn’t out until April, but if you’re still short of a Christmas present, this is well worth the hard cover it comes in. This quote, from towards the end of the book, is a brief and valuable axiom that is worth noting:

“If we remain grotesquely unequal, we shall lose all sense of fraternity: and fraternity, for all its fatuity as a political objective, turns out to be the necessary condition of politics itself.”

For some reason I remain a fairly infrequent cinema-goer, but Giorgos Lanthimos’s Kynodontas (Dogtooth) was a shocking and alienating experience that had some fellow members of the audience laughing in discomfort and others sitting stiff with tension. Werner Herzog’s latest, My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done, struck a pleasingly inane note in its treatment of a classic cinema situation: the hostage stand-off. The sound of Washington Phillips’s ‘I Am Born To Preach The Gospel’ emanating from a tinny radio over a long shot of gathered policemen, weapons cocked, (when at this point the audience already realises that the hostages are a pair of pet flamingoes), render this cliché gloriously ridiculous. On a much lighter note, Stéphane Aubier and Vincent Patar’s Panique au village (A Town Called Panic) had all ages reeling at its slapstick, claymation comedy:

Finally, the runaway album of the year in terms of how often I piped it into my ears, was Joanna Newsom’s Have One on Me. Managing somehow to follow up the twee coarseness of The Milk-Eyed Mender and the breadth and scope of Ys with a triple album of tight songs that demonstrate a noticeably stronger and more mature voice, Newsom proves herself to be an undeniably masterful musician.

And that’s all for this year. Here’s to new sights and sounds in 2011.

![Joanna Newsom, Have One On Me [album cover]](/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/JOANNA-HAVE-ONE-ON-ME1-324by324-80e25c.jpg)