Notes on notes in London

I was in London on Tuesday last week to attend Getting It Right? Performance practices in contemporary music, a day of talks and discussions on performance, composition and all the ways the two interact at LSO St Luke’s. Organised by Julian Anderson and Guildhall School of Music and Drama, the various speakers included Helmut Lachenmann, David Alberman, Michael Finnissy, Rolf Hind and Diego Masson, providing a variety of perspectives on the challenges of new music.

Keynote Speech: Helmut Lachenmann

Kicking off the day was Helmut Lachenmann, 75 this autumn and undoubtedly one of the greatest proponents of extended techniques and new sounds. His talk combined tales of his own experiences as he struggled with players who faced ‘not only technical but also psychological problems’ with his unusual sounds and some more ideology-driven ideas about how and why he feels compelled to implement these techniques. He described his shunning of tape for manuscript (and penning the moniker of ‘musique concrète instrumentale’), because sound broadcast by loudspeakers was ‘not so dangerous as it could be’, ‘you have only loudspeakers — like a photograph — this is a handicap’. He stressed throughout however that

It’s not the problem to find new sounds […] The problem is to find a new way of listening and if you can find a new way of listening you can do it on [sic] C major, because Palestrina once used it and later Richard Wagner — the same three notes.

This treatment of extended techniques not as ‘effects’ — which is how they are often classified in Anglophone circles — but as essential elements of the music, indicates the aim not for timbral inflection but for timbral composition, in which the types of sound (‘Klangtypen’) can be used to build musical structures; timbres become the main musical parameter instead of pitches, which reigned supreme in most earlier music. He maintains his belief in the power of tension and release, dissonance and consonance, which he learnt in harmony and counterpoint classes, but builds structures through a very different language:

It is so important to me that: It’s [extended techniques] not funny. It’s not expressionistic. It’s not a protest against society […] It is romantic, a sort of dissonance […] another pole to come back from to our centre.

He also touched on his belief that music can be divided into music as situation and music as text. So, Bach and Boulez, among others, he classes as musical texts that can be re-orchestrated and preserve their essential elements, whereas the opening of Beethoven 9 or the tremolos in Bruckner 4 are situations, the timbre of which are essential to the musical discourse and must be preserved. He spoke of aiming in his own music for such ‘meteorological situations’. (I also heard him speak about this last year and wrote about it here.)

Whenever I see or hear Lachenmann speak, I am reminded that this is a man of humour and humility, despite his frequent portrayal as the dour spectre of the ultra-modernist European avant-garde. He joked about the Darmstadt Summer Courses as ‘a nice zoo full of exotic animals,’ that he was ‘a victim’ of the trend there for titles that described the compositional process (e.g. Kontakte, Zeitmaße, not to mention Xenakis’s ST/48,1-240162 and similar works) in his cello piece Pression (which is “about” pressure). He cares about the sounds he writes, but the ironies of his career are not lost on him. ‘I feel a bit heroic now,’ he quipped when discussing the disrupted performances and disgruntled players he has faced. You can listen to his talk at the Slought Foundation from 2008 here to get a taste of what this man is like in person.

Playing Around: Performers and New Music

One of the revelations of the day was David Alberman. Second violinist of the Arditti Sring Quartet from 1985-1994 and currently leader of the second violins in the LSO, Alberman is gloriously direct, blending a fierce commitment to new music with a sarcastic wit that is well aware of the strong opposition such music often faces. With the Ardittis he premièred Lachenmann’s Second String Quartet ‘Reigen seliger Geister’ and has written about Lachenmann’s extended string techniques. His pragmatic approach to performance was impressive as was the time he clearly puts into a piece. He showed a version of a Ferneyhough score in which he had stripped out all the rhythmic brackets and calculated tempi for every group of notes to allow him to learn the speed of each small gesture (the proportions of the rhythmic brackets being essentially impossible to feel or calculate in performance). He stressed the importance for a performer of making their own musical decisions even if they diverge slightly from a literal reading of the score — that you should never play something in a way that you think is musically unconvincing. This might seem obvious, but it prevents the ‘Oh, it’s supposed to sound bad, so that’s fine’ attitude you sometimes come across and reminds performers that they bear a shared responsibility for the music with the composer.

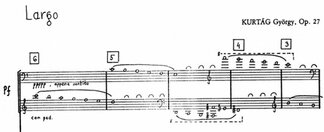

Both pianist Rolf Hind and conductor (and sometime percussionist) Diego Masson enjoyed telling some of the more humorous anecdotes from their lengthy careers. Hind spoke about working with György Kurtág on the opening of …quasi una fantasia…, for piano and chamber ensemble, a descending C major scale marked ppppp, Largo and con Ped.:

It transpired that Kurtág was actually looking for what Hind considered to be an mf, Andante, played legato with just a little pedal and Hind wondered whether perhaps there could be a divergence of perceived intensity and feeling, and actual acoustically accurate descriptions — so this music should feel very quiet and slow, but achieving this does not necessarily require it to be very quiet and slow.

Kurtág has something of a reputation for being perhaps not the most polite of composers towards performers after performances and Hind recalled the best compliment he received after a performance of …quasi una fantasia…, ‘You played the opening so beautifully, why do you play the rest like a pig?’ and anecdotes in a similar vein flowed from Diego Masson, who gleefully remembered his experiences in 1960s Paris. It should perhaps be more widely known that, according to Masson, Pierre Boulez supplemented his income during this period by playing a white piano in a Parisian strip club on a stage surrounded by naked women. I’m assuming he wasn’t playing Structures Ia. Masson said that they would play anywhere from money, whether it be modern music or radio jingles. He painted a somewhat anarchic picture of this time describing a recording session for Luciano Berio’s Laborintus II in which the jazz improvisations roughly at the middle of the work were recorded at 4 am as all the musicians were working in clubs until then and played clips from those sessions with Berio and Edoardo Sanguinetti (the librettist) performing some of the texts. The work had to be cut in two to fit onto an LP. How was it done? Side 1 ended and Side 2 started with studio sounds, the background chatter of people shouting pre-take, ‘Hey, pay attention!’ etc. Perhaps a forerunner of all those DIY-feel discs where you can hear the band chatting or joking before or after songs and it was the idea of a studio hand who just happened to be sweeping up while they were discussing the problem.

Building Beauty

The final Q&A session of the afternoon touched, among other things, on what beauty is or means to composers and musicians today. Lachenmann wrote about beauty as far back as 1976, but his thinking has always been influenced by Adorno and truly concerns the aesthetic rather than the beautiful, criticising Boulez and other avant-garde composers for turning away from thinking about such things. At St Luke’s it was clear that the linguistic complications of moving from German to English may have hampered his ideas coming across. ‘I like beautiness [sic] … but art is another thing,’ he said, but it seemed his understanding of ‘beauty’ perhaps equated better to ‘prettiness’ as he went on to describe Ennio Morricone and Henry Mancini as beautiful. Instead, ‘expression arises from the friction between the structure of a piece and the structure of ourselves.’ However, he did feel that the concept of beauty was helpful in working with musicians on his music, as persuading a performer to try and play a scratch or a distortion ‘beautifully’ chimed with their learnt practice of creating a beautiful tone. It fits with musicians’ ideas of the ideal or perfect sound, which they aim for when practising and playing.

Due to continuing fall-out from the Icelandic Ashpocalypse, the string quartet due to perform Lachenmann’s Third String Quartet, ‘Grido’, were lacking a cellist and we were treated instead to a public masterclass on the work. In some ways ‘Grido’ is the most traditional of Lachenmann’s three quartets, but it nevertheless poses challenges to the performer. David Alberman had described it earlier in the day as ‘a cathedral made up of bricks of sound, each brick of which leads into the next’ and it is this connection from sound to sound that is so essential to a successful performance. For some it may have been slightly uncomfortable to watch Lachenmann focus on one sound for minutes on end, asking the players to repeat tiny gestures until they precisely fitted together, but it is this painstaking work which makes a good performance of these pieces truly powerful and without which they very quickly fall down. It also drives home the importance to Lachenmann’s music of his own work with musicians. During his time in London he was working in small groups with players from the LSO who are performing his 2004 work for string orchestra, Double (Grido II), in June and one wonders how his music might survive once he is no longer able to be at rehearsals to explain these details. One hopes that committed players, like David Alberman, might be able to pass on their experiences, allowing the sounds and, more importantly, the musicality possible with such sounds to pass into standard performance practice, but it must be a fear that the knowledge, if it remains undocumented, might be lost. That fear is presumably why one holds conferences on contemporary music practice — to help spread knowledge of how and why to play this music. Musicians who have a true familiarity with this repertoire are few and far between and for every member of the Ensemble Intercontemporain, JACK or Arditti quartets, there are twenty traditionally-minded orchestral musicians. I hope and believe this is changing in conservatoires around the world, but only time can tell. In the meantime, those who care about this music have to ensure that it has every chance to speak for itself through high-standard performances and communicative playing. This music shouldn’t be sold as difficult or different, but as exciting and adventurous. And beautiful. For that is what it is.