264 Ways to Teach Max

Last semester I assisted Hans Tutschku with a class called Music 264 at Harvard University on improvisation with electronics, and we used Max as our main tool for students to build their own electronic “instruments.” Faced with students ranging from Max beginners to more experienced programmers, and wanting to spend as much time as possible making music, we needed a solution that would allow us to teach Max and simultaneously start exploring performance.

I wanted to write up some of our experiences, in particular focusing on a package of Max patches I built for the class called 264 Tools.

Getting Max to make music

The common approach to Max-learning of spending time with the famous tutorials can be helpful, but what to actually do with all this list processing, data type explanations, and mathematics can be less clear. It favours abstract thinkers and people with existing programming experience, but may be less useful to someone without that experience who wants to start making music. Besides, there are important reasons for not just sending someone off to learn by themselves or assuming prior knowledge.

Even if one is familiar with Max, it takes time to build things that can start to be musical and responsive. The process of moving from some kind of controller input, handling that data, and mapping it to some audio processing takes time. Building a delay unit or even a versatile sound file player takes time. It is possible to teach this type of programming in a semester, but probably not in a class where you want much music to happen.

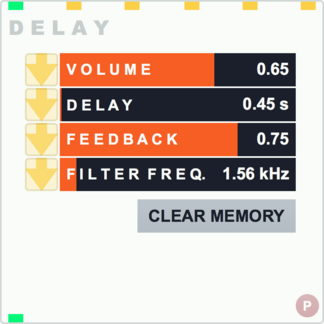

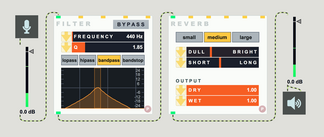

By building 264 Tools we tried to circumvent these challenges for both new and more advanced Max users. 264 Tools is a collection of patches for Max that can be loaded in bpatcher modules, providing ready-to-use playback, processing, and analysis tools with graphical interfaces. To any users who have played with BEAP, this will be a familiar approach — the difference being that where BEAP focuses on sound synthesis, the 264 Tools provide ways of working with recorded and live audio input.

These modules don’t do anything particularly new on the inside. Several rely heavily on amazing existing work by members of the open-source community: Ivica Ico Bukvic, Ji-Sun Kim, Dan Trueman, R. Luke DuBois (munger~); Patrick Delges (filesys); Randy Jones (yafr2); Miller Puckette, Cort Lippe, Ted Apel, Volker Böhm (sigmund~); Jean-François Charles (spectral freezing); Rodrigo Constanzo, and raja (karma~). 264 Tools builds on these by providing graphical interfaces and a consistent way of communicating between modules.1 This is also not an attempt to build a “complete” suite of tools for all contexts. There are some obvious limitations: we found it immensely practical to make everything mono, for example; and the GUI makes the modules less performant than they might be. (If you have any Max GUI performance tips, let me know!)

Learning by doing

The idea of teaching with 264 Tools was to have students spend as much time as possible inside Max itself, and have that time as musically focused as possible. They may not have mastered vexpr or figured out all the ins and outs of poly~, and certainly didn’t have to go through the pain of learning how pattrstorage works, but they had Max open, were creating and connecting objects, and started to understand how one might extend a module’s functionality by adding a few basic Max objects. Most importantly, from the first week we were working with sound. For people with backgrounds in music, the immediate feedback of hearing changes — rather than only understanding them abstractly — is very helpful.

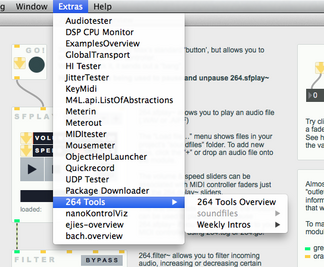

To keep students immersed in Max we exploited the strengths of Max’s package system.2 In particular, by using the extras directory in the package we could provide weekly patches introducing new modules that would appear in Max’s ‘Extras’ menu. These overviews provided explanations of each module’s functionality alongside demonstrations. Students could play with the demos and copy-paste bits of patch to their own projects. (I’m currently in the process of converting much of this to proper help files.) As of v0.13.0, these have been converted to help and reference files, so you can alt + click on a module and open its help file.

In our first week, 264 Tools consisted of a delay line, a sound file player, and a filter. We added a couple of modules each week from then on.3 As students built performance patches for class, it was astonishing to see the variety of possibilities they uncovered, even with a minimum of modules.

Beyond the laptop

The most obvious requirement in order to make the students’ patches “performable” in improvisatory contexts was a controller that probably wasn’t the laptop’s trackpad or keyboard. We ended up building lightweight performance kits, and chose Korg nanoKONTROL2 MIDI controllers for the students to interact with their patches. These provide 8 faders, 8 dials, and 35 buttons and send MIDI messages over USB.

We built all 264 Tools modules to work seamlessly with any external MIDI controller. You can quickly map a MIDI fader, dial, or button to your patch using the 264.midi-learn submodule, which is built into many of the 264 Tools.

Beyond the MIDI controller, we also provided students with a microphone, a single-input audio interface, and a loudspeaker. It was great to be able to keep each performer’s audio discrete using these performance kits, clarifying who was producing which sounds in group performances. This tied into a kind of “instrumental” thinking while developing 264 Tools: mono sources, processing, and output lent themselves to these multi-laptop performances. We couldn’t have done this without the amazing logistical support of our studio technical director Seth Torres. The performance kits he put together were just perfect.

Conclusions

By the end of the semester our students were able to perform improvisations, in some cases with no prior Max knowledge. While my teacher’s pride undoubtedly clouds my judgement, I was incredibly impressed by their work. I can also say that a classroom of captive beta testers, who are directly implicated in the tool you’re building, is an amazing resource to have. We finished up with 22 modules, from a MIDI-ready toggle to a pitch-tracker, and built a fairly easy to use preset system (I cursed pattrstorage so no-one else had to).

If you want to try out the tools for yourself, take a look at the installation instructions. Please let me know if you find any bugs (or just have questions).

I’d love to hear from anyone else teaching Max about their experiences, and if anyone does play around with 264 Tools, let me know what you think!

-

All 264 Tools modules understand messages in the range 0 – 127, mimicking standard MIDI, permitting easy communication between modules, as well as with any other MIDI device. ↩

-

First introduced with Max 6, packages have just received an exciting boost with the release of Max 7.1 and the new native Package Manager. We were using Nathanaël Lécaudé’s Max Package Downloader, which was a wonderful stop-gap before Cycling ‘74 introduced their own solution. ↩

-

An up-to-date list of the current modules can be found in the 264 Tools GitHub repository. ↩

Improvisers Listen #3:

Ute Wassermann

This semester I am assisting Hans Tutschku with a class at Harvard University on improvisation with electronics. I asked several improvisers to choose pieces of music that are important to them and their practice.

For the third edition of this series, Ute Wassermann has kindly agreed to share some of her favourite music. Wassermann has achieved recognition as a vocal artist, composer, and sound artist, with her personal, highly characterised, nonverbal sonic language. In addition to a richly developed range of vocal colours, she masks her voice with bird calls, resonant objects, and develops sound installations. She appears regularly as an improviser in London and Berlin, and has also premièred works by composers such as Ana Maria Rodriguez, Michael Maierhof, and Chaya Czernowin.

Wassermann’s selections introduce diverse vocal worlds, intersections of voice and technology, and various improvisatory practices.

Demetrio Stratos, ‘Flautofonie ed altro’ (1978)

Derek Bailey, ‘Improvisation’ (1975)

Janis Joplin, ‘Ball and Chain’ (1967)

Laurie Anderson, ‘O Superman (For Massenet)’ (1981)

Orchèstre Baka Gbiné, yelli (2008)

Kathy Keknek & Janet Aglukkaq, application for the 2008 Arctic Winter Games (2007)

Thanks so much to Ute for providing these insights into her listening world. Below is an example of her own live performances and you can find more on her Vimeo page.

Previously: Richard Scott, Vijay Iyer

Improvisers Listen #2:

Vijay Iyer

This semester I am assisting Hans Tutschku with a class at Harvard University on improvisation with electronics. I asked several improvisers to choose pieces of music that are important to them and their practice.

For the second edition of this series, Vijay Iyer has picked some of his favourite music with electronics. Iyer is a Grammy-nominated composer–pianist who has released 20 albums — most recently Break Stuff — and collaborated on many more. He was named DownBeat Magazine’s 2014 Pianist of the Year, a 2013 MacArthur Fellow, and a 2012 Doris Duke Performing Artist. In 2014 he began a permanent appointment as the Franklin D. and Florence Rosenblatt Professor of the Arts in the Department of Music at Harvard University.

Iyer’s selections range from instrument + laptop duos to studio tracks, including the late David Wessel’s innovative “SLABS” performance interface.

Wadada Leo Smith & Ikue Mori, ‘Demai’ (2003)

David Wessel, ‘SLABS Touch Pads’ (2009)

George Lewis ft. Vijay Iyer, ‘Interactive Trio’ (2012)

Mike Ladd, ‘Planet 10’ (2000)

Craig Taborn ‘Junk Magic’ (2004)

Thanks so much to Vijay for providing these insights into his listening world. Below you can watch video of an improvisation with saxophonist Steve Coleman and you can hear much more on his website.

Previously: Richard Scott

Next: Ute Wassermann

Improvisers Listen #1:

Richard Scott

This semester I am assisting Hans Tutschku with a class at Harvard University on improvisation with electronics. I asked several improvisers to choose pieces of music that are important to them and their practice.

First up is Richard Scott. Scott is a UK-born, Berlin-based composer and free improvising musician working with analogue modular synthesisers and alternative controllers, including pioneering work with the Lightning controller built by Don Buchla.

For our first instalment, Scott selected works by Cabaret Voltaire, Miles Davis, and the Spontaneous Music Ensemble.

Cabaret Voltaire, ‘Eddie’s Out’ (1981)

Miles Davis, ‘Pharaoh’s Dance’ (1970)

Spontaneous Music Ensemble, ‘Ten Minutes’ (1974)

Thanks so much to Richard for providing these insights into his listening world. Below is an example of his own live performances, or you can browse recordings on his Bandcamp page. Stay tuned for the next instalment!

Next: Vijay Iyer, Ute Wassermann