Ahead of Trio Atem’s performance at Kings Place next week, I thought I would share this essay on the work which brought them together: Helmut Lachenmann’s temA. It is a work that I imagine will have been a reference point or at least in the backs of composers’ minds as they wrote for the wonderful Gavin, Nina and Alice and explored the unusual combination of flute, voice and cello. It certainly was for me.

If you do want to hear the work before reading or — much better — coming to Kings Place on Monday, here is a recording by Boston’s Callithumpian Consort or I can recommend the recording by Ensemble Phorminx on Wergo.

This is a long essay and maybe it will be of more use after hearing a performance in digesting the work, but here it is for better or worse.

Helmut Lachenmann’s temA

In many ways the music of Helmut Lachenmann eludes elucidation through verbal media. His intricately notated scores reveal surprisingly little concerning the resulting sounds and structures to even an experienced reader and his music frequently fails to convey its full impact on recorded media, only operating fully functionally in the live performance for which it was conceived. Granted the latter has long been discussed as a problem, especially by aestheticians of classical and contemporary music, but it is a problem to a greater extent, very sorely felt in the case of Lachenmann’s music.

The reasons for these apparently incomplete transmissions (and conversely the presumably more creative than usual completion in performance of the instructions set down in the score) will be further discussed below, but it must be presumed that they lie somewhere in the physical aspect of performance — a physicality more vital to an audience’s perception of the music than is the case with audio more or less tailored for mass produced, and therefore disembodied, media.Given that even his own scores and carefully produced modern recordings do not adequately represent Lachenmann’s complete artistic vision, what hope does an analytical essay or diagram have in even half describing that performed-perceived experience? The following analysis makes no claim to be helpful to those unfamiliar with temA as performed. Instead, it is an attempt to understand how the effects of the work are achieved through a structural dissection of the sonic elements, their notation and their physical implications. It takes its lead from Matthias Hermann’s analysis of Lachenmann’s first string quartet Gran Torso.

Though as thorough an examination of performance techniques employed as lies at the core of that analysis is less helpful here given temA’s heterogeneous instrumentation, a similar tack will be taken in terms of grasping the ‘concrete’ sound-world employed and the journey through it offered to the audience by way of dramatic transformations of the sound material. This method is particularly useful in approaching the elements of Lachenmann’s post-serial musical language that break away from easily divisible hierarchies of pitch and rhythm and move towards what might be called timbral composition, though the associations that that term could suggest with Klangfarbenmelodie or other ‘colourful’ music is somewhat misleading. Here the timbre is not a colouring of musical material (harmonies and melodies, pitch sets and rhythmic rows perhaps), it is the musical material.Written in 1968, temA, for flute, voice and cello, is one of Lachenmann’s break-through works in terms of developing his early aesthetic ideas and style. Described variously as marking ‘the beginning of Lachenmann’s maturity as a composer’ and ‘the first work to demonstrate Lachenmann’s mature aesthetic ideas and techniques’, it is also one of the first works in his output to have been performed regularly until the present day.

It has been recorded twice; first in 1994 by members of Ensemble Recherche for the now defunct Montaigne Auvidis label and in 2009 on a disc by Ensemble Phorminx for German contemporary music label Wergo.Lachenmann has described temA, a single movement work lasting roughly a quarter of an hour, as ‘probably one of the first compositions in which breathing is explored as an acoustically mediated energetic process’.

The title plays on the German words ‘Atem’ (breath) and ‘Thema’ (theme), making it clear for even an audience member without recourse to programme notes that the work’s theme is breath. Lachenmann has acknowledged that others had examined ‘the same phenomenon from various different perspectives’ (he mentions Heinz Holliger, Vinko Globokar, Mauricio Kagel, Dieter Schnebel, and specifically Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Hymnen and György Ligeti’s Aventures), though he suggests they came to such similar interests independently of one another. Lachenmann is right to recognise his predecessors and contemporaries. Writing at the same time as Lachenmann penned the quoted note on temA, István Anhalt also identified the trend for ‘new compositions for the voice that use it in ways other than exclusively in the usual singing mode’, including ‘such marginal sounds as coughing, sighing [and] audible breathing’, which burgeoned from the mid-1950s onwards, listing over 60 composers he believed to be representative of the trend by the mid-1960s, a trend that perhaps confirmed Roland Barthes’s belief that ‘the human voice is […] a site which escapes all science, for there is no science which exhausts the voice’.There are relatively few works involving voice in the authorised list of Lachenmann’s compositional output, which numbers fifty-four works to date. Three works involving the voice, Consolation I, Consolation II and temA, stem from 1967-68, a time that might be identified as an international, intellectual crisis period, but also — and not necessarily unconnectedly — a time that can be described as a period of vital development for Lachenmann the composer. After these years of intense engagement with the voice Lachenmann didn’t return to it as a central focus of a work until the 1990s with „…zwei Gefühle…“, Musik mit Leonardo (1991-92), which incorporates two speakers of fragmented texts into a large ensemble, followed by his opera (or ‘music with images’) Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern (1990-96). Though a few works in the intervening years do involve voice — notably Kontrakadenz (1970-71), which incorporates some voices recorded onto tape, and Salut für Caudwell (1977) in which the two guitar soloists recite fragmented texts that foreshadow the speech of „…zwei Gefühle…“ — there is a noticeable defining, exploring and exhausting of vocal possibilities in the three early works, which leads one to speculate whether they were perhaps fundamental to Lachenmann’s transition into maturity as an instrumental composer.

Piotr Grella-Możejko writes that ‘for decades, the vocal medium served avant-garde composers in times of doubt and trial’, suggesting that when using a text it can ‘be considered a carrier of formal continuity and unity, […] a skeleton around which the flesh of the piece is built up’.

This thesis is extremely convincing when applied to the two Consolations. Both are small-scale choral works, the first for 12 voices and 4 percussionists and the second for 16 voices a capella, which set short texts rich in phonetic resonances — an extract from expressionist playwright Ernst Toller’s Masse Mensch and an 8th-Century prayer, the Wessobrunner Gebet, respectively. Disassembling their respective texts through phonetic analysis that aims to reveal an inherent logic of sound construction, the Consolations might be said to put into practice the theory set out eight years earlier in a lecture Lachenmann wrote for his teacher and friend Luigi Nono to give at the Summer Courses for New Music in Darmstadt, which defends such dismantling of texts (criticised by Stockhausen) with reference to the historical removal of semantic meaning from and phonetic treatment of texts, with examples from Gesualdo, Gabrieli, Bach and Mozart. The text of Consolation II, a meditation on finding God in the nothingness before time, is dissolved into a shuddering landscape of letters, hissing with a hollow wind, shivering with rolled ‘R’s, stuttering away into the nothingness where God can perhaps be found, ending on the ‘t’ of ‘Gott’, not sung but struck: two fingers coming together in a quiet clap. While hardly revolutionary — similar phonetic treatment of texts had been in use for almost a decade by Nono, Berio and Ligeti among others — the Consolations mark an important personal stepping stone for Lachenmann towards temA and further on towards his mature style. In particular, the ‘instrumental vocalisation and vocal instrumentalisation’ illustrated both by the ending ‘t’ of Consolation II and the consistent attempts to bring vocalist and percussionist sonically closer in Consolation I, would prove a vital resource in the writing of temA.Despite their similarities, temA bears several marked contrasts with the Consolations. The simplest is the lack of pre-existing text. Instead of choosing a ‘skeleton’ to flesh out, all the vocalisations — whether phonetically disintegrated or semantically intact — are written specifically for certain passages and therefore ‘do not have to be understood by the listeners since they serve to modify the exhalation in a specifically conceived manner’.

As we shall see though, this abnegation of potential semantic transmission is not necessarily entirely consistent and definitely not holistic. The second difference between the Consolations and temA is an uncomplicated but decisive question of instrumental resources. The choral medium allowed for extremely textural text setting that opened up large aural spaces and environments, whereas the constraints of the solo voice related via breath to the flute related via line to the cello in temA, while benefiting from the reduced distance between voice and instrument exploited in the Consolations, require an economy of treatment and tight focus on sound qualities to achieve the sort of timbral cohesion advocated in Lachenmann’s 1966 essay ‘Klangtypen der Neuen Musik’. Grella-Możejko describes this as ‘linear music at its most compromising’ — there is nothing to bind these three instruments together except the very delicate equating of sound-types to create the sort of timbral continuum that would become fundamental to many later works, especially those scored for chamber ensembles. As it transpires, this allying of sound-types is not exclusively a matter of aligning sonic similarities, but also of drawing parallels between the actions of the performers. This is a compositional approach, which Lachenmann later verbalised (and has since frequently restated) saying, ‘composing means building an instrument’.temA explores the possibilities offered by musicians and their instruments not just in terms of sounds available, but also in the physical relationships these various methods of sound production exhibit. For the first time, Lachenmann is able to make the performers’ physical effort the work’s theme both through its directly resultant sound and through the use of sound material that intimates particular physical processes. This may sound loftily theoretical, even fanciful, but it is in fact essentially visceral. One of the paradoxes of musical aesthetics is how on the one hand, the development throughout the 19th-Century into the 20th of the belief that somehow music offered the most sublime of forms beyond physicality — to the extent that, to use Walter Pater’s oft-quoted axiom, ‘all art constantly aspires towards the condition of music’ — led to a denigration of the physical element that is perhaps more obviously present in certain folk idioms; while on the other hand, the repeated affirmation, since the advent of recording techniques and especially electroacoustic music, that these ghosts of physical performance are strongly lacking an element which can be no dimension other than the physical (no matter what claims are made for ‘aura’ or other such terms).

This lack of immediacy or clear perceptibility of the causality of sounds and music has long been a weight on composers working with disembodied media. This paradox suggests that the physical aspect of performance cannot be so easily dismissed as only a small or inconsequential part of the musical experience.In attempting to highlight both the importance of a gesture as ‘an energy-motion trajectory which excites the sounding body’ and the difficulty an electroacoustic composer faces in the lack of an (observable) ‘agent’ to perform the physical counterparts to their music’s sounding gestures, Denis Smalley may give us a key to understanding something of Lachenmann’s thinking.

Lachenmann has described his music from the late sixties onwards as ‘musique concrète instrumentale’, adapting Pierre Schaefer’s name for tape music using recorded ‘concrete’, i.e. real world, sounds as its compositional material, but ‘instead of using the mechanical actions of the everyday instrumentally as musical elements, for me it was about recognising the instrumental sound as a sign of its production method’. (Lachenmann was familiar with studio techniques after working at the IPEM-Studio in Ghent in 1965, during which period he wrote his only solo tape work Szenario.) In his 1983 commentary on temA, he acknowledges the work as marking ‘the first step for me towards a “Musique concrète instrumentale”’. It is fitting then perhaps, given the direct line drawn by Lachenmann between early fixed media composition and his own instrumental music, that Smalley’s writing on electroacoustic problematics describes so clearly some of the fundamentals of Lachenmann’s approach.In addition to Grella-Możejko’s contention that the voice can provide support to a composer in the process of development and experimentation due to its potential for providing reliable structural cohesion outside of what might be termed, slightly misleadingly, the ‘purely musical’ grammar of a work, there may be another good reason as to why Lachenmann chose the voice and the breath as the subject of temA’s experimentation or why it transpired to lend itself so well to the development he achieved with this work.

Smalley comments on the power of the voice in music, stating that ‘vocal presence […] has direct human, physical and therefore psychological links’. For Lachenmann these ‘physical links’, which Smalley proposes survive even the complete disembodiment encountered in electroacoustic music, may have proved useful in explicating the physical processes of sound production that he wished to draw attention to, our deep engagement with this corporeal energy conversion aiding his aesthetic intentions.Though not an area of theory Lachenmann has ever discussed in detail, there is an affinity between his wish, based on post-Adornian concepts of alienation, to subvert traditional instrumental performance technique to reveal the effort of the musician — symbol of the repressed servant to the bourgeoisie, ordered in the 19th-Century concerto tradition to complete feats of cruel agility and difficulty beneath a façade of painless ease — and the theories of corporeity of Marcel Merleau-Ponty.

Merleau-Ponty describes the body as ‘a knot of living meanings’, an idea that lends credence to the possibility that the physical actions of musicians could be understood as a matrix of meanings bearing the potential for their structural perception. Particularly relevant for our understanding of the physical aspect of Lachenmann’s work is the idea that ‘the meaning of a gesture intermingles with the structure of the world that the gesture outlines’ and that linguistic gestures ‘just represent ways for the human body to celebrate the world and ultimately to live it’. This also ties in with Lachenmann’s advocacy of ‘music as existential experience’. The voice’s eventual movement from spoken or sung bearer of extrinsic semantic content to a subverted instrument, taking its place as part of a self-defining structural grammar constructing its own intrinsic value, over the course of temA points as it were to Lachenmann’s subsequent, voiceless works, moving away from the Ur-vocalisation supposedly at the root of music’s inception, away from music as message and music as speech, towards his aesthetic ideal of music as a holistic experience as affecting and meaningless as walking through a landscape in the rain.All these many factors may have led Lachenmann to choose the instruments he did or may have benefitted him in ways he did not realise at the time, but nevertheless there are some serious hurdles to be overcome in creating a work for these instruments. Some of these same problems also present themselves to the analyst. In the analysis of comparable works such as Pression (1969/70), for solo cello, and Gran Torso (1971/72), for string quartet, extensive charts of the techniques employed are used to draw convincing conclusions about Lachenmann’s structure of constantly evolving sound materials and physical actions.

The heterogeneous instrumentation of temA prevents a simple analysis of playing techniques as each instrument has its own specific gamut of traditional and extended techniques, which can of course bear various relationships to those of other instruments but are essentially different. Thus, frustratingly given our establishment of the importance of gesture and physicality to the work’s conception, the easiest way to carry out a survey of the work’s progression is to speak in terms of heard instead of performed, physical similarities.Given the theme of breath, it is unsurprising that actual human breath, physically related phenomena such as the flautist’s breath modified by the external body of the flute and acoustically related phenomena such as the pitchless breath-tone of the cellist’s bow-hair on the wood of the instrument body are systematically combined. This provides the possibility for a musical discourse that can move from breath — pure, modified or artificial — to pitch, via the gradual evolution of timbre from, for example, the vocalist’s pianissimo inhaled breathing (b. 41), to pitchless arco on the side of the body, on the bridge and on the tail-piece of the cello (bb. 43, 45 & 47 respectively), to a sul tasto pianissimo A high up the cello’s G-string and a breathy pianissimo E-flat in the flute (bb. 48-49), which culminates in a pure, sung D of the vocalist (bb. 49-50) which then itself is passed on for yet further development. Though the transitions are usually more complex aggregates of this type of process, similarly straightforward transitions between pitched and unpitched material can be found in the ‘flute solo’ of b. 64 and in the movement from an unpitched breathing (of the group as a whole) to pitch and back in bb. 159-168.

These sections containing long, undisturbed breaths form the work’s key resting points. The inhaled breathing repeated ad libitum by the vocalist in b. 41 — which Rainer Nonnenmann describes as a ‘Schlafkadenz’ (sleep cadenza), highlighting somewhat ironically the subversion of traditional soloistic resources — brings the work’s first point of stasis, but is also in many ways the work’s true point of departure.

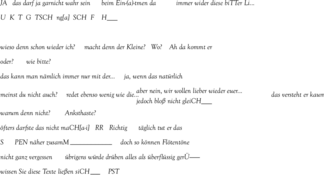

The work opens with a gasp and the first thirty or so bars are pointillist, filled with short gestures, clicks, solitary allophones, more gasps and the distinct feeling that the audience has been ushered in to experience a process that had already begun before they arrived. In b. 22, the vocalist is instructed that ‘all inhaled processes from here until b. 41 form a related series, the design of which should be determined by the conception of someone sleeping’. Bars 29-36 consequently begin with similar inhaled gestures, foreshadowing the arrival and stasis experienced in b. 41, while still surrounded by the variegated network of rapidly transforming short gestures and phrases in the flute and cello established at the work’s beginning. Having come through these forty bars of ‘foreplay’ we arrive at the gentle inhalations of the ‘sleep cadenza’. While static in the sense of repeating the same material, this bar is exemplary of the potential for drama through physicality. The act of breathing is ingrained in our experience of being, such that its fundamental rules of regular inhalation followed by exhalation followed by inhalation can form a universal play of expectation. The repeated inhalations of the sleep cadenza without the anticipated intervening corresponding exhalations cause a build up of tension and expectation to such an extent that the eventual molto calmo exhalation of the following bar can take on a weight that belies its quiet simplicity, acting as the gentle push which sets Lachenmann’s instrument rolling, re-starting the process of constant evolution, which gradually builds through bb. 43-66.The piercing shriek, which engenders a stream of violently rapid figurations in flute and cello in b. 67, and the clearly audible word ‘Luft’ (air) two bars later are probably the clearest delineators for the listener of the next substantial structural passage. Not until b. 79 does Lachenmann include the instruction ‘murmured dialogue between flautist and vocalist’, but from b. 69 onwards half-comprehensible snatches of semantically decipherable speech start to appear. As observed above, the performance notes instruct that the texts ‘do not have to be understood by the listeners since they serve to modify the exhalation in a specially conceived manner’, which indeed they do, but they nevertheless remain partially comprehensible and more importantly, at least to German-speaking audiences, highly pertinent in commenting on the issues raised in the process of their own performance. The first in this series of semantically relevant, self-referential texts is the previously mentioned exclamation of ‘Luft’ in b. 69. This reference to air clearly ties in with the stated theme of the composition. After this the following vocal material is to be found in bb. 70-102:

Nonnenmann highlights the intentional selection of phrases in this passage to ‘modify the exhalation in a specific manner’, for example ‘jedoch bloß nicht gleiCH’, which contains the hard ch, [x], which eventually consumes the text in b. 83.

Such a sound could be deconstructed as an exhaled [x] with disturbances in its onset or as a spoken phrase, which gets stuck on a recurring phoneme. This same technique can be found in most of the other text fragments used in this passage. Nonnenmann also suggests that the use of fragmented, phonetically suitable but partially comprehensible vocal material is a skilful ruse aimed at ‘sparking the attention and curiosity of the listener’, who is trained to listen out for meaningful speech by their everyday experiences. Thus, the listener can be drawn into the musical process and their increased attentiveness subverted to draw their attention to the sonic development in progress. This half-understood passage also seems to reflect Borges’s suggestion that the ‘imminence of a revelation which does not occur is, perhaps the aesthetic phenomenon’. This is emphasised by the final fragment ‘wissen Sie diese Texte ließen siCH’, a combination rich in the consonant [s] and a play between the [ɘ], [ɨ] and [i] vowel sounds, which carries the suggestion that the audience are about to discover what exactly the semantically discontinuous dialogue is all about — ‘did you know these texts were…’ — but is cut short by the flautist’s (phonetically related) ‘PST’ to which Nonnenmann has attributed the ironic interpretation that at the one point where ‘an apparently plausible communicative interaction between flute and voice’ is achieved, the dialogue breaks down, precluding the apparently immanent revelation of whatever it is that lies behind the present events.The held silence that follows the flute’s interruption of the voice gives way to a rattling, quadruple fortissimo in the cello and the music moves from the dialogue passage’s generally not particularly loud and never particularly extreme execution (since its screamed initiation in b. 67) to the Agitato/Feroce passages which provide the work it’s energetic core with a whirlwind of tremolandi, rapid scales, volatile swells of dynamics and sounds that exploit the extremes of physical pressure in all three instruments. This passage draws its energy from the ominous drone of bb. 108-114 marked ‘calmo ed intensivo’, during which the music seems to be gathering breath. In a way these bars echo the ‘sleep cadenza’ in their near stasis, which builds up an expectation of release. ‘Ponderous’ fpp accents in the cello count out time rather like the inhaled breaths that went before and for the first time Lachenmann employs what might be a familiar, old-fashioned technique in the use of a pedal point G in the cello, foreshadowed in bb. 97-100 and held and rearticulated throughout the thirty-two crotchet beats of bb. 108-112 until its dissolution in a gust of harmonics (b. 113), which launches the onslaught of expanding gestures that drives the music to near breaking point in b. 147.

The rapid alterations of dynamic in bb. 120-124 and the build up of spiralling, tremolando scales in bb. 135-146 are as much as anything else a wave of physical violence, which seems to be forcefully dragging the voice away from its natural methods of sound production — an assault protested by cries of ‘HALT!’ (stop) and ‘BITTE’ (please) — and towards an alienating array of sounds created by putting excess pressure through the vocal mechanism. This results in the breaking apart of the continuous musical fabric in b. 147 as the cello’s excess pressure on the strings between bridge and tailpiece brings a screeching halt to proceedings leaving the voice seemingly ‘stuck’, only able to manage the occasional croak. The extremity of these actions and their impact are a source of pride for Lachenmann who believes their shock value lies not in the ‘deformation of the sound, as such ‘disassociation’ was widely tolerated as a humorous, Dadaist or expressionist element’, but in the logic of their containing form.

Having shattered the linearity pushed to extremes in the Agitato/Feroce passages, Lachenmann manages to gradually reassemble a semblance of coherence with a return to natural breath and its instrumental variants in bb. 159-168, but this soon gives way once more to highly pressurised processes and as the wood of the cello’s bow is pressed through the bow-hair against the instrument’s body causing a sound strongly reminiscent of cracking wood the music seems to grind to halt for good (b. 179). Once more we are ‘stuck’.And that it would seem would be that, were it not for a small resurrection and in the context of an extended, unfamiliar sound-world of alienated performance techniques it is a greater miracle for its content. The final nine bars represent in some way the emancipation of the full and warm instrumental tone from its exhausted familiarity through the rigorous examination of the physical objects — human bodies, flute and cello — that work to produce it. This ‘coda cantabile’ marked as ‘sempre dolcissimo quasi lontano’ seems to exist beyond the rest of the work in time but also seemingly in the physical dimension.

Before we conclude our examination we should turn briefly to the pitched elements. It is not worthwhile carrying out a thorough pitch analysis for temA in this context as pitch relationships bear more or less no structural importance in comparison with contrast and development of timbral and physical aspects. In the places where they do form part of the clear fabric of the work, such as the abovementioned G-pedal, they are determined by the physical characteristics of the sounding bodies — the G for example is chosen for its properties as an open string with the flexibility to swell with bow pressure. Elsewhere pitch is often used in rapid figurations more as a gestural element than as a melodic or harmonic idea (e.g. bb. 67-68 or bb. 143-146). Where longer lines do meet and form what might tenuously be described as harmonic instances they are usually rich in minor seconds and often form longer-term progressions that are effectively slow gestures in pitch space. For example the following pitch content from bb. 48-55:

Given the above discussion, the following approximate structural schema might be proposed based on the idea that there are coherent areas of activity interspersed with more obviously transitional or directional material, all of which can be described in terms of the physical processes related to the voice that they act out or evoke:

| bar(s) | content |

|---|---|

| 1-28 | Introduction |

| 28-40 | transition |

| 41 | ‘Sleep Cadenza’ |

| 42-67 | transition |

| 68-102 | Dialogue |

| 103-112 | gathering breath |

| 113-146 | Agitato/Feroce (Scream) |

| 147-158 | Paralysis I |

| 159-168 | Instrumental Breath |

| 169-178 | transition |

| 179 | Paralysis II |

| 180-188 | ‘Coda cantabile’ |

This schema suggests various interpretations. A traditional idea of climax would suggest that the gradual progression to a climax of energy and effort at the end of the Agitato/Feroce passage indicates that this point is the core of the work, to carry on our corporeal metaphor, it is the work’s navel. It seems a convincing argument that what occurs from b. 147 onwards is, to raise the spectre of causality, heard as a direct consequence of the aggregate of energy, effort and pressure that preceded it and that the overload of these in the Agitato/Feroce passage violently forced open the surface of music itself causing usually hidden realities to reveal themselves. Perhaps this is a fanciful conclusion, but it seems to be the only explanation for the very definite otherness acquired by the plain, hummed concluding bars — the modification of perception through structural rigour.